Table Of Content

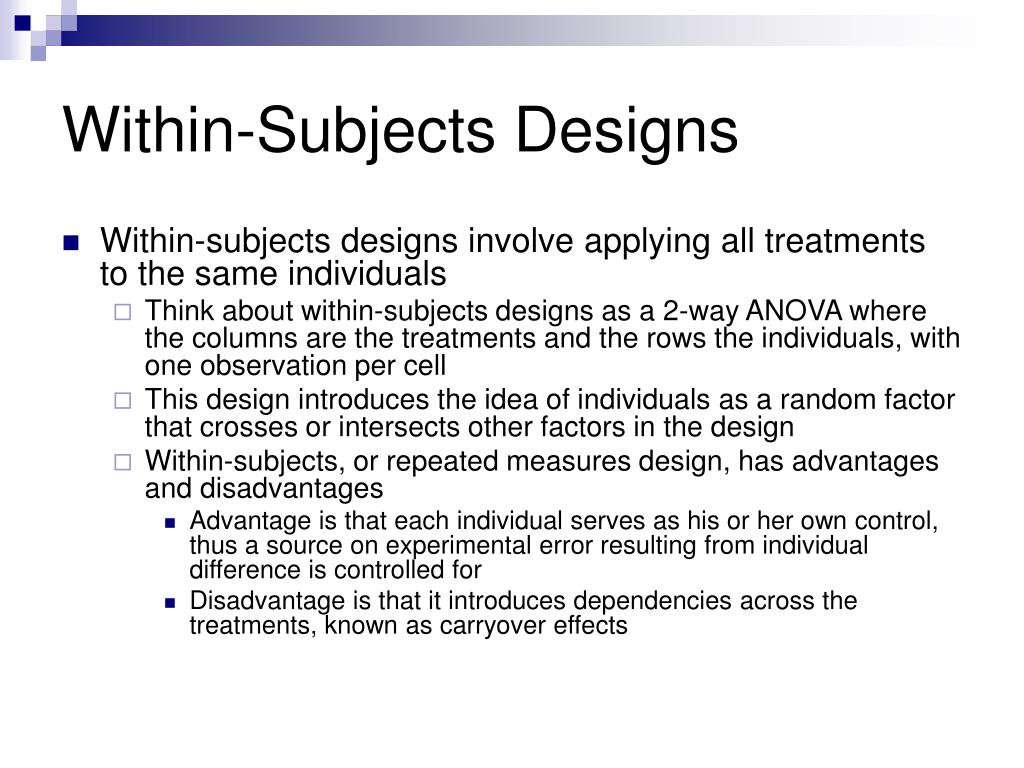

Because you expose each subject to each condition, you get less error variance caused by natural differences in subjects. Essentially, the subject is their own control group, and differences in responses to the exposures cannot relate to extraneous subject characteristics such as age, upbringing, education, and so on. Such a single-process account of the present findings would begin with the assumption that items vary in strength even prior to encoding (Jang, Wixted, & Huber, 2011; Mickes, Wixted, & Wais, 2007; Wixted, 2007). At study, the strength of any given item would then increase dependent upon idiosyncratic factors such as the amount of attention or rehearsal dedicated to that item. Production would then provide a further increment to the strength of the produced items. By virtue of this increment, the proportion of weak (familiarity-based) and strong (recollection-based) memories should be greater for produced items than for nonproduced items.

Individual differences may threaten validity

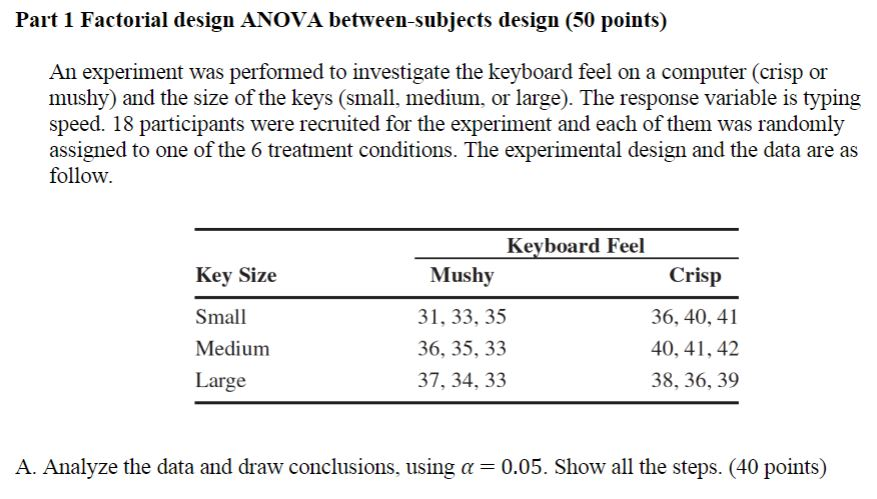

A 2 means that the independent variable has two levels, a 3 means that the independent variable has three levels, a 4 means it has four levels, etc. To illustrate a 3 x 3 design has two independent variables, each with three levels, while a 2 x 2 x 2 design has three independent variables, each with two levels. Just as including multiple levels of a single independent variable allows one to answer more sophisticated research questions, so too does including multiple independent variables in the same experiment. For example, instead of conducting one study on the effect of disgust on moral judgment and another on the effect of private body consciousness on moral judgment, Schnall and colleagues were able to conduct one study that addressed both questions. But including multiple independent variables also allows the researcher to answer questions about whether the effect of one independent variable depends on the level of another. Schnall and her colleagues, for example, observed an interaction between disgust and private body consciousness because the effect of disgust depended on whether participants were high or low in private body consciousness.

Factorial Designs

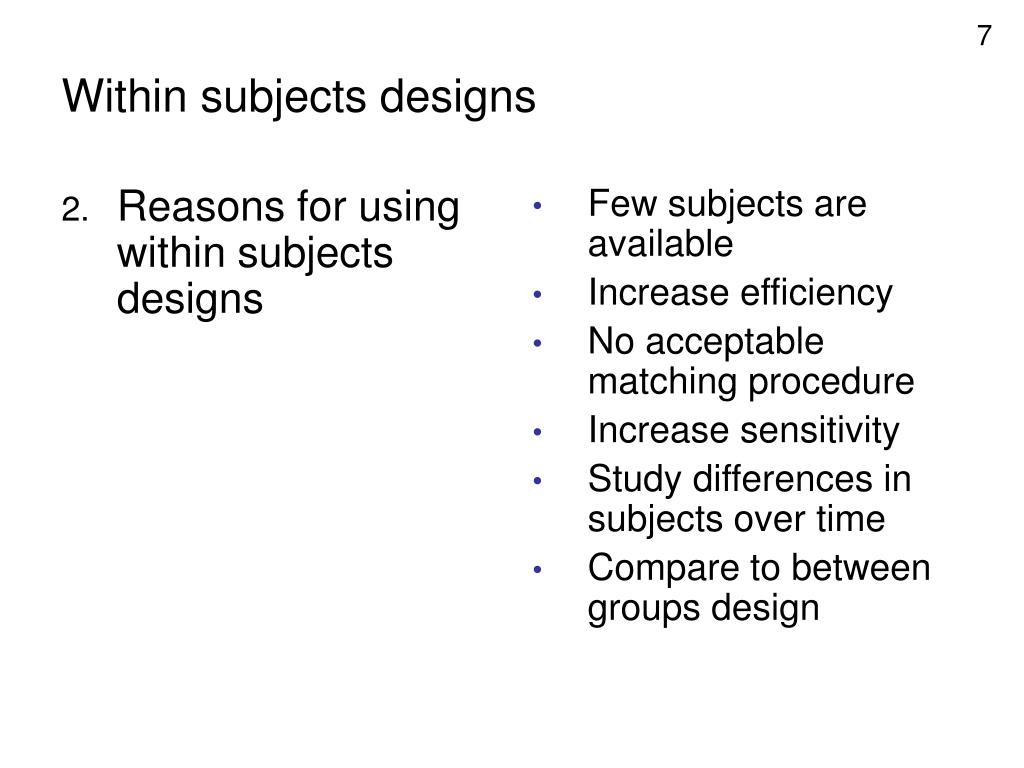

It offers a shorter study duration, prevents carryover effects, and reduces the risks of internal validity. However, it also requires a larger sample of participants and more resources, and personal differences may affect its validity. Another vital difference between the two is that in a within-subjects design, each subject experiences all conditions. Therefore, the researcher tests the same subjects repeatedly to examine the variations between the conditions.

Method

For example, an effect of participants’ moods on their willingness to have unprotected sex might be caused by any other variable that happens to be correlated with their moods. If the sample size is large enough, if the assignment is indeed random, the initial differences between the subjects will be controlled, and confusion of subject variables and conditions will be avoided. Thus, the logic of the random approach is flawless; the problem is to provide a positive answer to both its. Using random assignment to group the participants is recommended to certify that the reference line subject qualities are analogous across the groups. You can also apply masking to ensure that the subjects will not work out if they are in the control or experiment group.

For example, the parents of higher achieving or more motivated students might have been more likely to request that their children be assigned to Ms. Williams’s class. Or the principal might have assigned the “troublemakers” to Mr. Jones’s class because he is a stronger disciplinarian. Of course, the teachers’ styles, and even the classroom environments might be very different and might cause different levels of achievement or motivation among the students.

Non-Manipulated Independent Variables

Demonstrating a treatment effect in two groups staggered over time and demonstrating the reversal of the treatment effect after the treatment has been removed can provide strong evidence for the efficacy of the treatment. In addition to providing evidence for the replicability of the findings, this design can also provide evidence for whether the treatment continues to show effects after it has been withdrawn. One way to improve upon the interrupted time-series design is to add a control group. The interrupted time-series design with nonequivalent groups involves taking a set of measurements at intervals over a period of time both before and after an intervention of interest in two or more nonequivalent groups. Once again consider the manufacturing company that measures its workers’ productivity each week for a year before and after reducing work shifts from 10 hours to 8 hours. This design could be improved by locating another manufacturing company who does not plan to change their shift length and using them as a nonequivalent control group.

Attractiveness for clients

However, our between-subjects experiments resulted in a different pattern—with production increasing only the proportion of weak memories (familiarity-based) with no impact on the proportion of strong memories (recollection-based). Taken together, a single-process interpretation of our findings would therefore conclude that production strengthens both weakly and strongly encoded items when manipulated within-subjects, but only weakly encoded items when manipulated between-subjects. Because we can see no reason to expect that production would preferentially benefit weakly encoded items in between-subjects designs, we are presently unable to reconcile a single-process account with our data and therefore prefer the dual-process account described earlier. Nonetheless, a single-process explanation for the design effects in the present experiments may emerge in the future. We first analysed the probability of participants scoring a hit or false alarm by collapsing remember and know responses into a single binary response. We further adapted our coding to mathematically centre item type such that it was −0.5 for foil items and 0.5 for study items (as opposed to the usual 0 and 1).

If it really is an effect of the treatment, then students in the treatment condition should become more negative than students in the control condition. But if it is a matter of history (e.g., news of a celebrity drug overdose) or maturation (e.g., improved reasoning), then students in the two conditions would be likely to show similar amounts of change. This type of design does not completely eliminate the possibility of confounding variables, however. Something could occur at one of the schools but not the other (e.g., a student drug overdose), so students at the first school would be affected by it while students at the other school would not. That being said, this type of experiment design can be impacted by which order you expose the participant to the different conditions.

Do you feel safe with your robot? Factors influencing perceived safety in human-robot interaction based on subjective ... - ScienceDirect.com

Do you feel safe with your robot? Factors influencing perceived safety in human-robot interaction based on subjective ....

Posted: Thu, 18 Nov 2021 08:38:10 GMT [source]

In a basic pretest-posttest design with switching replication, the first group receives a treatment and the second group receives the same treatment a little bit later on (while the initial group continues to receive the treatment). In contrast, in a switching replication with treatment removal design, the treatment is removed from the first group when it is added to the second group. Once again, let’s assume we first measure the depression levels of patients with depression and students with depression.

Researchers test the same participants repeatedly to assess differences between conditions. A total of 369 students enrolled at University of Toronto Scarborough signed up to participate online in exchange for partial course credit of which 184 participated in the aloud condition and 185 participated in the silent condition. The data were screened to exclude participants who did not complete the entire task, took part more than once or reported any extraexperimental activities that might have influenced their performance (e.g., speaking with a friend, taking a midexperiment break). These exclusion criteria resulted in 269 usable participants (129 in the aloud condition, 140 in the silently condition). Having established that production affects both recollection and familiarity when manipulated within-subjects, but affects only familiarity when manipulated between-subjects, we next provided a replication of the between-subjects pattern using a larger sample. We chose to replicate the method of Experiment 2b rather than Experiment 1b because confidence ratings are easier to explain than remember-know ratings via written instructions.

Experiment 3 provided a final replication of our between-subjects design in a large, online sample. We then conducted a meta-analysis to compare formally the magnitude of the production effect captured by each dependent measure as a function of study design. The primary disadvantage of within-subjects designs is that they can result in order effects. An order effect occurs when participants’ responses in the various conditions are affected by the order of conditions to which they were exposed.

By supporting this framework, we will provide a more coherent explanation of why the between-subjects production effect arises, and why it is less reliable than the within-subject production effect in recognition memory. The between-subjects study design has its own set of advantages and disadvantages, which can make it more suitable for certain situations while posing challenges in others. Since each participant only experiences one condition, you don’t have a risk of order effects or changes in performance due to the order of presented conditions. This can be particularly useful when exposure to one condition might affect responses to the other condition.

However, these study designs can have multiple treatment conditions, so a study with three conditions. If one of the independent variables had a third level (e.g., using a handheld cell phone, using a hands-free cell phone, and not using a cell phone), then it would be a 3 × 2 factorial design, and there would be six distinct conditions. Notice that the number of possible conditions is the product of the numbers of levels. A 2 × 2 factorial design has four conditions, a 3 × 2 factorial design has six conditions, a 4 × 5 factorial design would have 20 conditions, and so on.

Carryover effects are the lingering effects of being in one experimental condition on a subsequent condition in within-subjects designs. These include practice or learning effects, where exposure to a treatment makes participants’ reactions faster or better in subsequent treatments. In sum, reading a word aloud improved familiarity to a greater degree than reading a word silently, casting new light on past concerns regarding the diminutive nature of the between-subjects production effect in recognition (see Fawcett, 2013). Our present findings provide the first evidence that production enhances familiarity when manipulated between-subjects, but does not impact recollection—supporting our dual-process account of the production effect in recognition memory. Our findings likewise echo the failure to observe a between-subjects production effect in studies using recall as their dependent measure (e.g., Jones & Pyc, 2014)—which might also rely on recollection. The left column depicts the back-transformed estimated proportion of old, remember and know responses for Experiment 1b as a function of production (silent, aloud) and item type (foil, target).

So while complete counterbalancing of 6 conditions would require 720 orders, a Latin square would only require 6 orders. When the study is within-subjects, you will have to use randomization of your stimuli to make sure that there are no order effects. Experiments that include more than one independent variable in which each level of one independent variable is combined with each level of the others to produce all possible combinations. Such as, for example, qualitative differences between the subjects, which can greatly affect the objective test results. For example, all participants can be tested either using the mobile version of the user interface or without using the mobile version of the user interface, and in the office or at home, during work or weekends, etc.

However, instead of dividing participants into two groups, you ask all participants to try the first option first and then the second. Then you compare the test results to determine which interface was more efficient and user-friendly. Along with the methodology between subject design, it always goes within subject design.

No comments:

Post a Comment